Much of what OMRUM reviews and analyzes is the total amount of money spent on healthcare in the United States but also who claims what percentage of each dollar. Based on our historical trend, the United States will spend, for the 1st time ever, over $5 trillion on healthcare in 2025. As demonstrated earlier in the OMRUM article from December 2024 (The Death Spiral), a critical graphic will again be revisited.

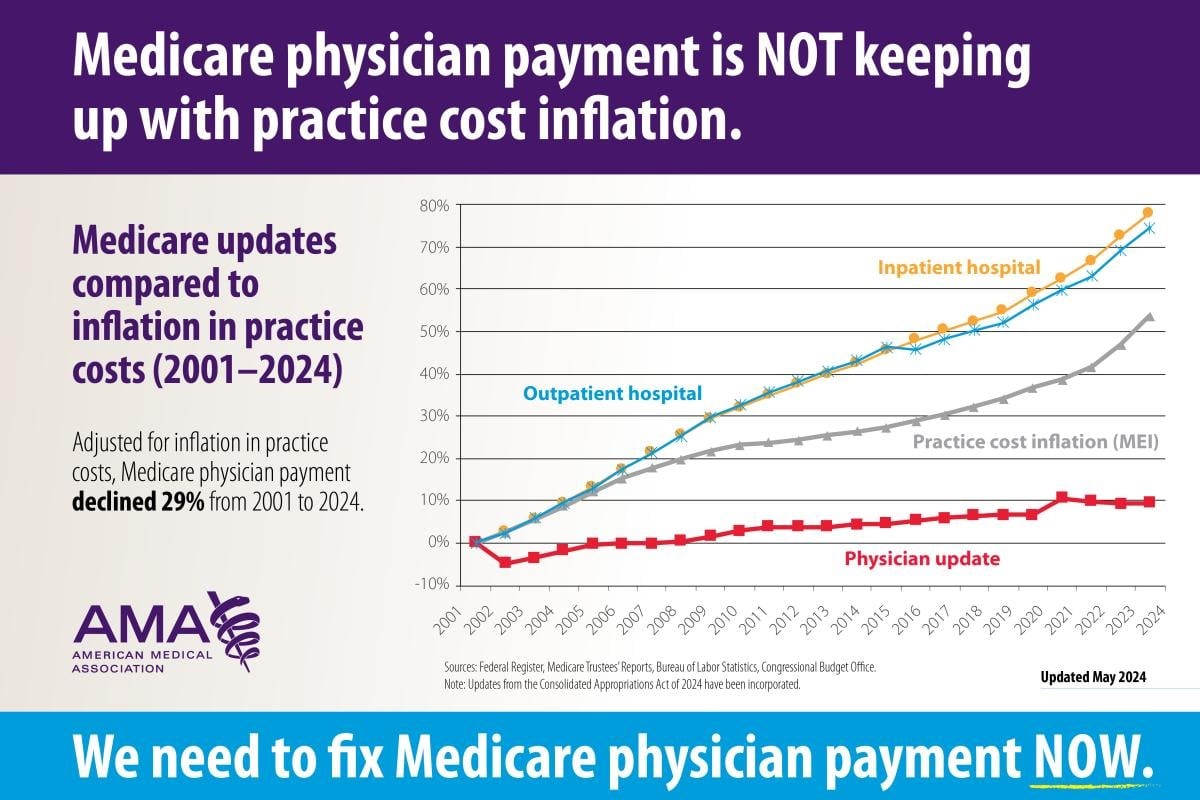

Once again, this extremely important graph (from the AMA in May 2024) will be reviewed, now with the goal of explaining how hospitals are hiring more and more physicians as their employees. As will be explained later, this author believes that this is one of the most dangerous trends in medicine today. Specifically, physicians with patient care responsibilities should not be employees of a hospital as it creates a serious conflict of interest.

Since the turn of the millennium through 2024, Practice Cost Inflation (the cost of treating patients-gray line) has increased almost 55% above baseline while physician payment for services (red line) has gone up only 10%. Thus, the reimbursement per service has gone down circa 40%. However, independent physicians still must pay their employees, malpractice insurance, rent/mortgage, medical equipment, and so on. Note that all of these have gone up in cost. Thus, the physician normalized reimbursement (which is what remains after these costs, i.e. after everything else is paid) has gone down each and every year for approximately the last 25 years.

Now, let us review the trends of hospital reimbursement over the last 25 years.

The top 2 lines of the graph represent the change in payment to hospitals for inpatient (yellow line) and outpatient (blue line) services. Inpatient generally refers to care of patients admitted to the hospital, outpatient care refers to everything else. Over the last 25 years, the reimbursement to hospitals has gone up substantially. One can easily see that hospital payments has significantly outpaced practice cost inflation.

In summary, when accounting for inflation, hospitals are receiving significantly more lately for services rendered and physicians substantially less for their services rendered. Hence, physicians have to do substantially more work to maintain (normalized to 2001) their income.

The next question is how have hospitals managed to outpace reimbursement is compared to inflation? As Hamlet famously said, “there’s the rub”.

There are a number of elements to this question but our focus will now be on something called the “facility fee”. For outpatient services, the hospital will not only charge public and private insurances the cost of performing services but they will add something which private practices cannot, a facility fee. The facility fee is an additional charge which hospitals add to their insurance claims. This charge covers the cost of the physical space in which services are given, the cost of equipment used, and other items. So, if one were to undergo an appendectomy by a hospital employed surgeon, the outpatient (after discharge) follow-up would include the addition of a hospital facility fee for the office visit. Interestingly enough, even if a physician employee saw the patient in an office owned by the hospital but not physically connected to it (a remote site), the hospital is allowed to add a hospital facility fee to that service just as if the patient were physically within the hospital. However, if a surgeon unaligned with the hospital treated the patient and saw the patient after discharge, the unaligned surgeon is not allowed to charge a facility fee.

Let’s review one such facility fee documented by the Charlotte Ledger. In its article “When Your Doctor’s Visit Comes with a Hospital Fee-but No Hospital” by Michelle Crouch (9/23/24), its research showed that for ultrasound studies in North Carolina adding a facility fee, the cost jumped “from $191 to $460.” Yes, adding the facility fee more than doubled the cost of the procedure compared to an outpatient, non-hospital facility. As noted previously, private (non-hospital employees) physicians have to pay their employees, malpractice insurance, rent/mortgage, medical equipment, and so on from the professional fee alone. Thus, a hospital’s facility fee reimbursement is a gold mine.

So, what do the asset rich hospitals do to the ultra lean private physician practices? The hospitals buy them. Once bought, the hospital can bill for their newly acquired practice as if it was attached to the hospital. Again, this means that the hospital can charge a facility fee on top of the fee for physician’s professional services which may double the cost to the patient for the same service. The hospital recovers the cost of their purchase of the private practice quickly and repeats its cycle with its next practice purchase.

Let us again review the (now) 2 reasons why hospitals should not be allowed to hire physicians. First, while physicians are bound by oath to offer the patient the best possible care, as an employee of the hospital, a conflict of interest immediately applies. The hospital will frequently pressure physicians to support the hospital financially by improperly admitting patients, running extra tests, and the like (as was discussed in the article from our December 15, 2024, A Modest Proposal (with apologies to Mr. Swift)). That article specifically references one situation in which a hospital administration demanded that the ER staff admit more patients to the hospital even though it was poor patient care and entirely unnecessary. However, the hospital wished to increase its margins by admitting marginally ill patients which had lower overhead. Just to be clear, this practice is extremely illegal. In our current article, we see the second reason why physicians should never be hired by a hospital. That is because under our convoluted medical system, off-site physicians who are hospital owned may charge patients both a professional service fee and a facility fee. Physicians not controlled by a hospital will only charge the traditional professional service fee which is far less expensive for the patient. So with physicians aligned with the hospital, costs increase significantly with no benefit.

So, if one does not glean anything else from the above, the one thing which should be borne in mind is that when the hospital signs the physician’s paycheck, there is an enormous pressure on the physician to offer a return on investment to the hospital at the expense of patient care. Any possibility for this conflict of interest to occur should not be allowed.

The remedy for this policy error has a few elements. First, either the facility fee must be paid to both the hospital and the private practice (quite costly to the consumer), or neither should receive it. Second, hospitals must not be allowed to hire physicians as the conflict of interest between patients’ interests and the hospitals’ interests is too great. Finally, physician reimbursements must be adjusted according to practice inflation or else the relentless ratcheting downward of reimbursement will compel the physician pool to quit their careers early, set up concierge practices, or transition to nonclinical careers leading to an even greater mismatch of physicians needed to physicians available.

All of the above is straightforward to remedy, if the will exists to do so.